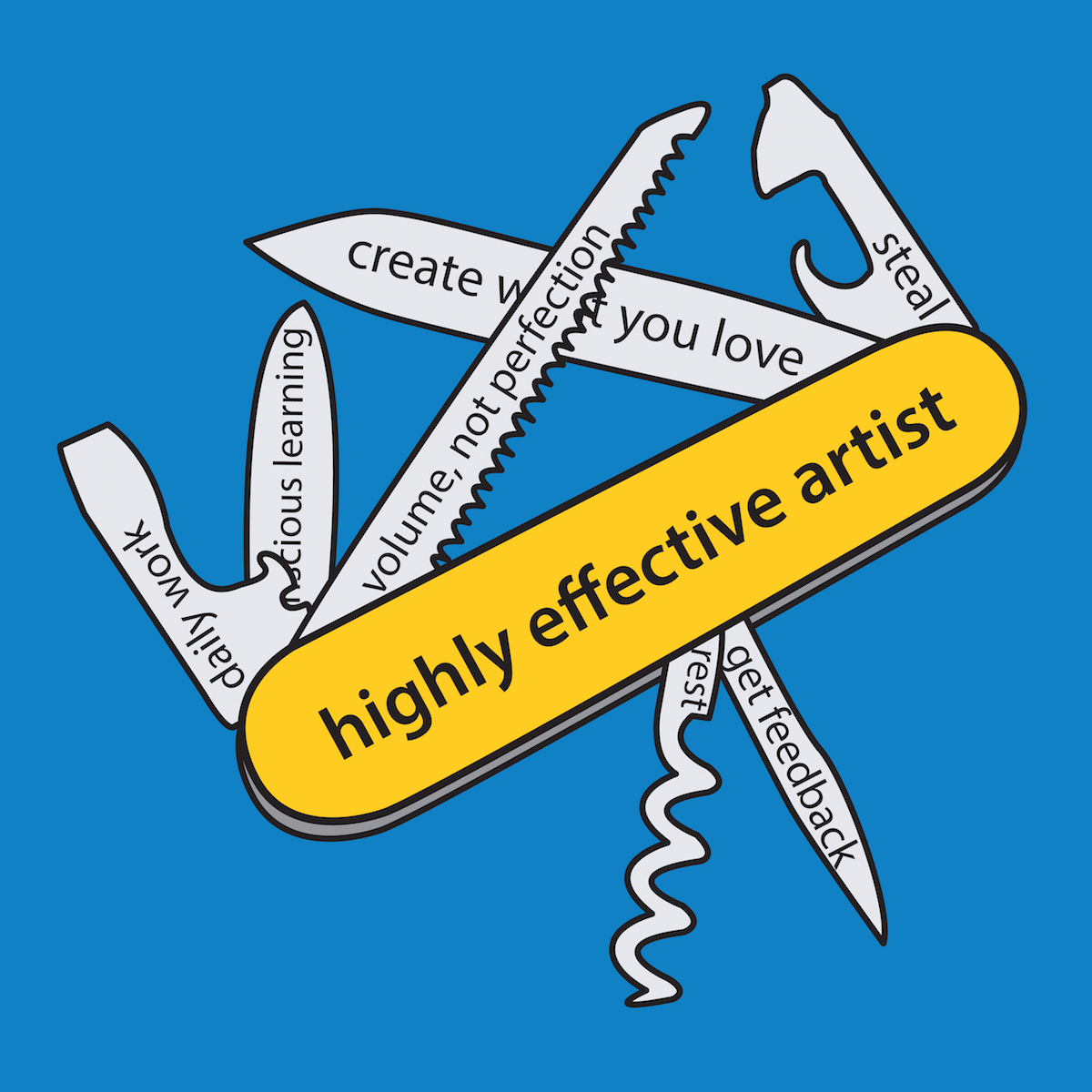

As a continuation of the last post on rigor and creative block, I’d like to discuss creativity with the 7 habits of highly effective artists as outlined by Australian 3D artist Andrew Price as the springboard. I jotted down thoughts and tangents on each of the seven points—a sort of supplement to the talk, if you will. Here they are:

1. Daily work

Yes!! Even if it’s just 30 minutes daily, that’s better than cramming it all in one day. Sure, when I’m on a roll, pulling an all-nighter and finishing something in a spurt of inspiration can be fruitful—but to develop my artistic skills over the long-term, it definitely needs to be a daily practice.

This is central to me as a musician and to how I matured as a singer. Of course, I let myself off the hook and skip practice some days, but I am aware of the cost—I can never get that 30 minutes in the past back, not even in exchange for 3 hours in the future. So that often gets me up and practicing (now playing zither instead of singing), even if just a few times through a piece.

I can never get 30 minutes in the past back, not even in exchange for 3 hours in the future. That thought gets me up to practice.

I’ve been learning that it’s good to balance rigid discipline with a bit of leniency at times and remember to be kind to myself too. I’m not a robot and it’s fine to allow myself occasional days of rest during my work week.

Let me add that I’m equally strict about making sure to take time off on a regular basis. On my Sabbath, there is very little that can get me to open my laptop and pull me away from the realm of sewing on missing buttons, watching Korean television with my grandma, and having an ice cream cone in the AM.

2. Volume, not perfection

I think this is true. Each project, audition, etc. is an opportunity to grow as an artist whether the end result itself is successful or not.

For me, I have many ideas, good and bad, and I follow through on a lot of them, so inevitably some lead to success and some to failure. It’s not necessarily about being as prolific as I can and hoping something sticks—it’s about trying whatever I want without worrying too much about the result. That leads to more volume, and pushing myself to try things outside of my comfort zone as an artist, which is less scary when I don’t have the looming need for perfection.

3. Steal

“The only art I’ll ever study is stuff I can steal from.” —David Bowie

In music composition class long ago, I learned that the act of composing is an act of rewriting something that has already been written (Writing Degree Zero by Roland Barthes). There is nothing new under the sun. We are simply rewriting the same note, redrawing, remaking.

It’s about taking what’s been done and redoing it your own way, sincere in your effort and with unwavering commitment.

4. Conscious learning

Mindless practicing is not always helpful, I agree. For a time-oriented person like me, this can become more of a problem than getting myself to practice. I’ll punch in and out, like it’s a job (which it is too), and log my hours for the day, but it may not have been the kind of practicing most beneficial to me at that point. It’s difficult to break away from routine when it’s time for a check-in lesson, a change in structure, or just a moment to stop and make sure I’m on the right track.

There’s a time for mindless learning too, like in music for finger memory and certain aspects of developing technical facility. I can think of at least a couple of musicians at the top of their game who have mentioned they work or went through a period of working with the television on.

I want to add that it’s productive, probably necessary, to disrupt the hum of the regular routine of practicing and learning once in awhile by throwing in a monkey wrench. Unexpected circumstances and disastrous situations have trained me to become a polished performer, unfazed by distractions, and a flexible artist, able to adapt to whatever I’m working with.

5. Rest

What the speaker says about leaving work alone after working on it for a period and coming back to it—yes yes yes. On a day-to-day scale, this is why unplugged time (for me, running when it’s not cold out) is so valuable. That’s when my brain starts making connections and I think I’m going to do this, and this, and this! Which feeds back to number 2, volume. More ideas connecting → more work to do → more output.

And it’s like you’re working on the project as the creator and then coming back with a fresh perspective as the editor.

6. Get feedback

It was interesting to hear in the video that the number 1 computer graphics school’s top grads are noted for seeking criticism and actually listening to it. I wouldn’t point to that as the common quality of star alums from the arts schools I’ve attended.

Setting aside the one-in-a million genius who has had the opportunity of cultivating his/her talent, the way I see it, it’s a combination of networking, aggressively pursuing opportunities, hiring the best-connected publicist (in the short-term at least), etc. and less about whether a person is 5% more talented than another. Once you have achieved artistic excellence at a certain level, it’s not about who can play or sing better.

Once you have achieved artistic excellence at a certain level, it’s not about who can play or sing better.

And many people who are not experts in a particular arts field can’t tell whether one person is marginally better from a technical perspective than another. In fact, I’ve been baffled to see that some people can’t seem to tell the difference between a local high-school “star” level act from the real thing. What I should make of this, I don’t know. So much of art has to do with nuance—what do you do when you find that audiences are unable to perceive the nuance?

Anyway, it hadn’t occurred to me that the most successful artists seek criticism and listen to it. Maybe it’s less applicable in my specific musical field, more applicable in computer graphics creation and the digital arts.

Getting feedback and workshopping pieces are certainly key. When I truly collaborate with a partner on a project, I find that it turns into a completely different project than what either of us would have come up with on our own and the end results are often surprising in a good way. But collaborating can be a challenge so it’s nice to have a solo outlet for when I don’t want to deal with anybody else, at least momentarily.

Getting feedback and workshopping pieces are certainly key. When I truly collaborate with a partner on a project, I find that it turns into a completely different project than what either of us would have come up with on our own and the end results are often surprising in a good way. But collaborating can be a challenge so it’s nice to have a solo outlet for when I don’t want to deal with anybody else, at least momentarily.

Having the right teachers to give feedback is also of utmost importance. I owe so much of my growth as a musician to the numerous teacher-mentors who have poured into me their time, their care and love, and their thoughtful and honest feedback. After a while, I started to internalize what they taught me and had a sense of what they might say about a piece without them actually being present. When I got to that point where I could hear their feedback in my head, I knew I was on the right track. (Check out this interview with acclaimed saxophonist Mark Turner. He mentions how you know you’ve really studied someone if you know how they’d respond in a certain situation—in his case, he passed the test once he could play what his three influences, Coltrane, Joe Henderson, or Warne Marsh, might play over a certain chord progression, being able to emulate each of them with their distinct approaches.)

I’m thinking persistence has a lot to do with it, though if you’re taking silent steps and making progress that few others are witnessing, are you still a successful and effective artist?

7. Create what you love

Even if doing one thing, do what you love, says Price. Sure, I think that is ideal, but it’s not always practical. It’s really up to each artist to decide what is important to them—being able to make only the kind of art they’re interested in even if it means driving a cab for a day job (e.g., NEA jazz master/saxophonist Dave Liebman in his early days) or taking gigs you may not care about artistically to pay the bills, as long as you can make a living doing something related to your art.

On the flip side, if you do a lot of things, your heart might be in all of them but the word is that people won’t trust you on any of them. I’ve been advised away from this (but I’ve been ignoring it because I want to do everything I want to do). Even within the relatively small realm of jazz, for example, you can’t be a bossa nova and avant-garde singer who also does indie rock on the side. That’ll be confusing to your audience and they won’t understand what you are good at.

Doing too many things is too complex for casual audiences to process.

And that brings us back to branding! Doing too many things (even if you do many of them very well) is too complex for casual audiences to process. Your brand is more effective if you are known for one thing, sending one message.

These are my personal experiences with creativity and perhaps they differ from person to person. If you think differently or have additional thoughts, I’d love to hear them so please feel free to comment.

Illustration for Tronvig Group by author

Ask for help.

We are kind, thorough and ready when you are. You just need to ask.