I visited the Center for Civil and Human Rights as part of the American Alliance of Museums‘ annual meeting, which doubles as a celebration of museums everywhere. I first attended an evening reception and walked through the museum very impressed. The brand new center provided a striking contrast to the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Visitor Center that I had toured the day before.

Something about the experience bothered me, but it was a party and I took in everything on offer, trusting in the brand of museums to steer me true, inform me, and of course, guide me in the direction of thoughtfulness.

It was not until the next day that I began to fully process what I had experienced. I was in a car going to another event when I found myself telling a story to another conference attendee. I was retelling the story of a 1964 Nobel Prize Dinner (also retold in the New York Times article announcing the opening of the museum last year). Then I caught myself. “Why am I telling this story?” It’s a story related to the content of the museum that my listeners surely had never heard before. It’s a compelling and retellable story with a happy ending, but who are the heroes of this story? Atlanta, yes. But really it’s the Coca-Cola Company. Why am I telling a Coca-Cola Company brand story after visiting the Center for Civil and Human Rights? This is when I decided to go back and visit again.

I am not a museum critic, but I do feel compelled to share what I experienced and pose some questions from my particular perspective as a marketer and museum lover.

My passage through the Center for Civil and Human Rights

Walking past the colorful lobby mural, the first exhibit I saw in detail was the wonderful collection of original manuscripts and other documents from the Morehouse College Martin Luther King, Jr. Collection. The second was the main first floor exhibit “Rolls Down Like Water: The American Civil Rights Movement.”

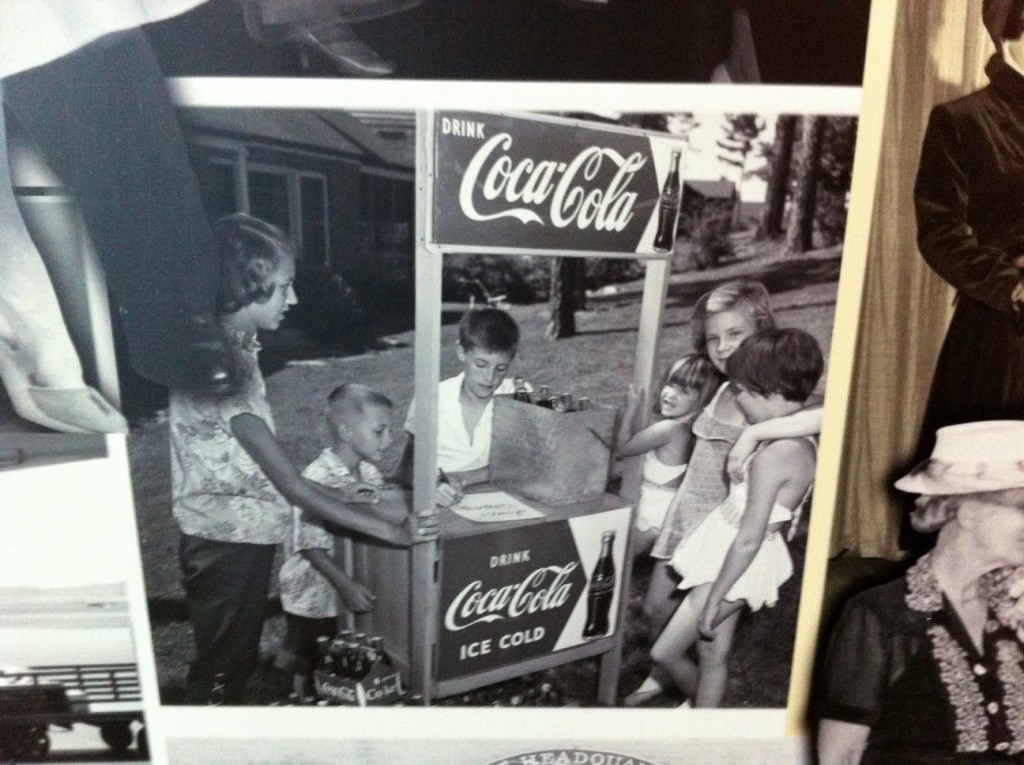

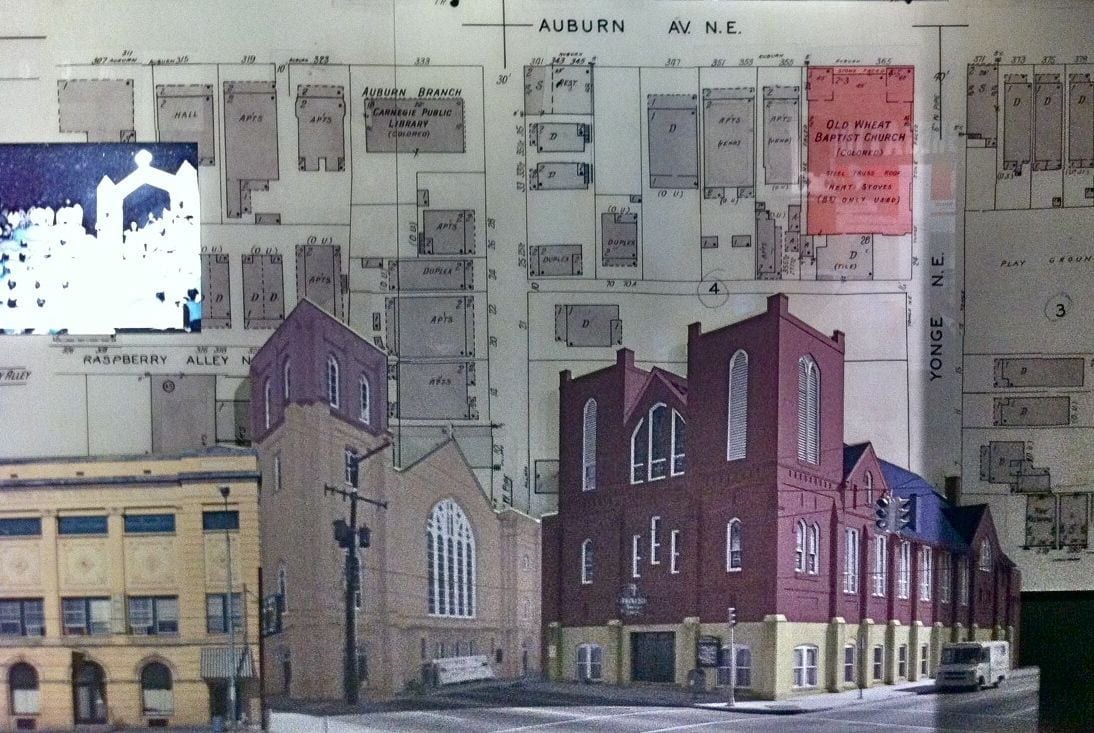

As you enter this gallery, there is a “Colored” wall and a “White” wall with photographs comparing the differing realities of life in 1950’s/early 1960’s Atlanta for blacks and whites. On the “White” wall I noticed a couple of photographs that prominently feature Coca-Cola. It was on my second visit that I looked more closely at the “Colored” wall asking myself, “Was Coke something these two worlds shared?”

Yes.

Returning to my first experience, I then entered the room most talked about among the museum professionals: the soda fountain counter in which you don headphones and experience the abuse of a civil rights activist who is trying to sit peacefully at a whites-only counter. I nearly missed it in this short yet intense experience, but my friend who came back with me the second time pointed out that the first sound you hear on the audio is that of a soda being uncapped. Phsht! It’s a familiar and comforting sound, followed by much emotion.

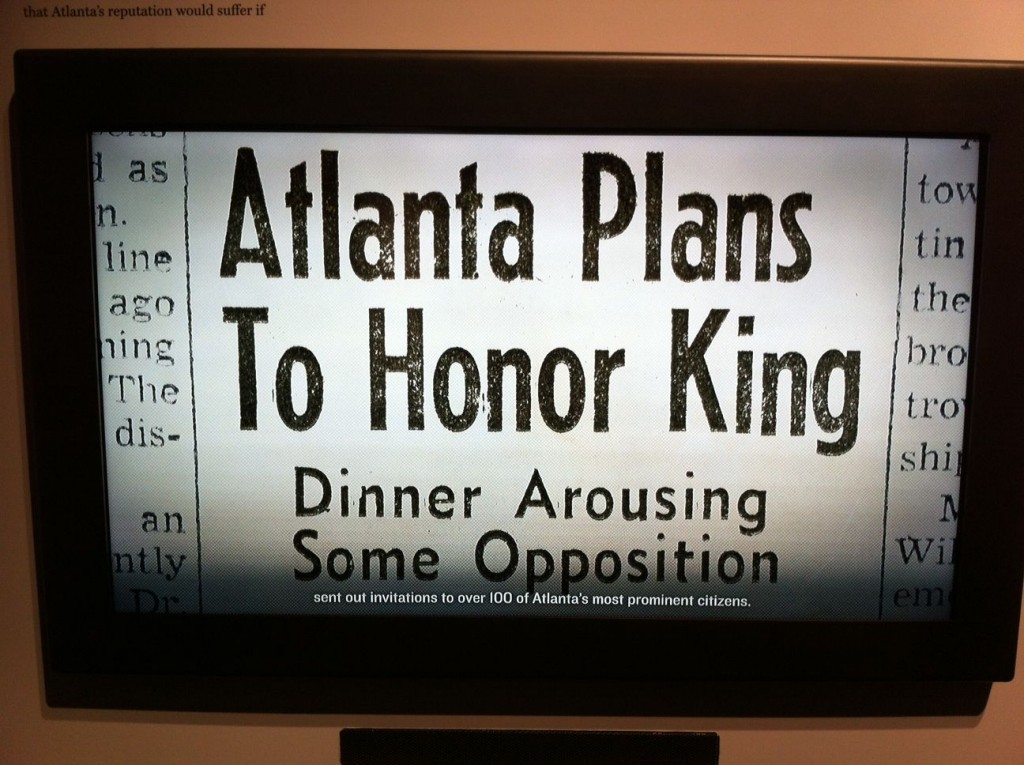

As I recovered from the effects of the soda fountain counter experience, I needed some straightforward narrative content to restore my emotional equilibrium, so I walked across the room to a large wall panel with an embedded video and quietly took in the story told there. This was the story I brought with me out of the museum.

Please note that this is one of the most powerful things a brand can do—give you a single story worth retelling. In this case it was a story of how Coca-Cola executives saved the day in 1964 for a Nobel Peace Prize reception banquet honoring Martin Luther King Jr. I remembered the details and literally repeated the whole thing to my peers the following day, when prompted by a question about the night before. It was a new story to me and thus, a part of the civil rights movement narrative that I could assume others did not know.

It was also arguably trivia.

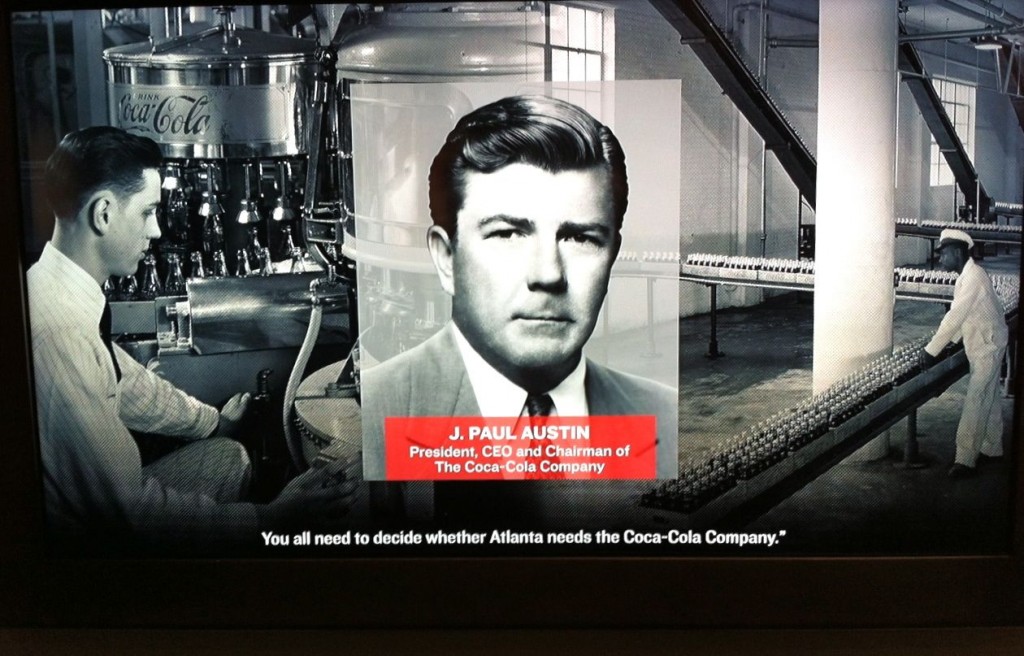

But the New York Times also retold the same story straight from the video with no commentary as if from a prepared PR script: “The event was apparently rescued when the president of the Coca-Cola Company, J. Paul Austin, called an emergency meeting of the city’s business leaders, declaring: ‘The Coca-Cola Company does not need Atlanta. You all need to decide whether Atlanta needs the Coca-Cola Company.’ Two hours later, the dinner sold out.”

Viewed from my vantage point as a marketer, this is a damn well-placed piece of brand advertising.

It ties in with the history of Atlanta, with the Coca-Cola Company, and with the preeminent leader of the Civil Rights Movement. It certainly made me feel good about the Coca-Cola Company, while illuminating nothing about Martin Luther King, Jr. and little about the Civil Rights Movement. I understood the Coca-Cola Company to have been an early and active supporter of Martin Luther King Jr. and it became an unlikely hero of the bigger story. Martin Luther King Jr. is gone now, but the Coca-Cola Company, his supporter, is still here in Atlanta doing good things like supporting this museum. This story is undoubtedly true, and I do not mean to postulate any sinister motive.

I don’t drink Coke, but this brand story that palpably connected one American icon, MLK, to another, Coke, was intoxicating. I can only imagine its effect on the line of Coca-Cola fans I could see lining up to go into the World of Coca-Cola not 100 yards away …

Incidentally, it was also during my second visit that I consciously noticed the museum’s color palette for the exhibit designs: fire engine red and white. Hmm.

Incidentally, it was also during my second visit that I consciously noticed the museum’s color palette for the exhibit designs: fire engine red and white. Hmm.

The advertorial museum

The Center for Civil and Human Rights is a 43,000-square-foot facility that sometimes refers to itself as the National Center for Civil and Human Rights. It is located in downtown Atlanta, an important city in the history of the U.S. civil rights movement and the home base of Dr. Martin L. King, Jr. to whom a large portion of the museum is devoted.

According to the New York Times, it cost 68 million dollars to create. The question of money is very real for nearly all museums. Practically everything costs money directly or indirectly, so naturally, museums must explore all manner of means to feed this ravenous beast.

Visiting the the Center for Civil and Human Rights, whose corporate sponsor list is quite impressive, I feel that I saw money buy something more than I had seen elsewhere. It was not patronage or sponsorship but something subtler, and for me, rather disturbing.

The only description I can muster in thinking about it is: “advertorial.”

An advertorial is an advertisement in the form of editorial content. The term “advertorial” is a blend of the words “advertisement” and “editorial.” Merriam-Webster dates the origin of the word to 1946 (Wikipedia).

Advertorial: an advertisement in the form of editorial content. The term “advertorial” is a blend of the words “advertisement” and “editorial.”

Advertorial in its pristine form—where there is no label indicating that it is in fact “advertising”—can be very effective. Advertorial allows a brand to leverage a framework that already has the trust of the consumer and can therefore effectively bypass the advertising defense mechanism that many people use to protect themselves from advertising messages.

Advertorial also has the potential to undermine consumer trust—not in the advertiser, but in the vehicle that carries it. Trust in the editorial integrity of a publication has traditionally been protected by a “wall” between editorial content and advertising. If you translate this concept into the museum world, one could think that there should be a natural barrier between curatorial and development. The analogy is not perfect, but I think we can agree that a key role of curatorial is to develop content for a museum that is aligned with that museum’s mission, with the development commissioned to fund that effort, not to direct it. I realize that the world is not so pristine. But I do trust, by default, that a museum’s content is the inspiration and carefully thought-out work of the directors and curatorial departments and not a carefully planned marketing message designed to effectively deliver a sponsor’s message.

The power of advertorial

Is this what is happening at the Center for Civil and Human Rights? Is one of the central takeaways (the one I got and the one the New York Times got) a brand story for the museum’s key corporate sponsor? Or am I just imagining things?

This basic question leads to others: Why does Atlanta have two museums dedicated to telling the story of Martin Luther King Jr.? Why is one rather neglected, underfunded, and falling apart, and the other a very shiny, state-of-the-art facility ostensibly dedicated to the same story?

All museums have a point of view whether they acknowledge it or not. In our work, we counsel that this position be exposed and that it actively serve to support the institution’s core values and its mission. If I were to reverse engineer the mission of the Center for Civil and Human Rights based on my personal encounter with the museum, I could postulate something like the following:

Civil rights was an important struggle in American history. Thanks to visionary leaders like Martin Luther King Jr., aided by some of the important citizens of Atlanta (including the executives at Coca-Cola), we have overcome many of our shortcomings as a nation. But the struggle continues … elsewhere. It continues in many other realms and in many other places. But here in America, here in Atlanta, on the issue of civil rights, we’re pretty good.

It says nothing like this anywhere in the center of course, and this may not have been their intent, but it sure was my emotional takeaway. And I observed that it was also the takeaway of some of the children I saw passing through on my second daytime visit.

I listened to some 5th graders as they talked excitedly about their experience. One explained the huge map of the world at the back of the second floor galleries to his classmate: “The countries in yellow are free, the orange ones are partially free, and the countries in red are not free.” he says. “See, we live in America where we are free.” His friend frantically looks for a country on the map, saying, “Where is Greece?” He asks, “Is it a free country too?” He finds it and is palpably relieved. “I’m from a free country too!” he exclaims.

Introspection? No. Assurance that we are a great country (and that Atlanta is a great city)? Yes.

I could almost hear the walls whisper to me as I walked out of those clean, climate-controlled surrounds and into the bright Atlanta sunshine … “Enjoy your civil and human rights. You’ve earned them. Relax now. Be happy.” And a little quieter still, a cold soft drink opens. Phsht! All may not be right with the world, but here it’s good.

More thoughts on this map—The World Map of Freedom—which I also found troubling, here.

Welcome to the future?

In thinking about my experience and my own takeaways, I have a few general questions.

Question: Can genuine curatorial independence be a real thing? Am I just being naive? Am I overreacting?

Question: Is the “advertorial museum” an anomaly or is it becoming more common? Outside of commercial entertainments, such as the longtime GE-sponsored Carousel of Progress at Disney, I had not experienced this phenomenon before. Never had it been so overt as to be noticeable. Should we expect more of this from other museums in the future?

Question: The Center for Civil and Human Rights clearly works as an inspiring destination for many of its visitors. Perhaps Disney has inured us to a new reality in which corporate sponsorship is just an accepted part of our cultural landscape. It is not always a bad thing. A friend reported to me about this museum in glowing terms, “My African-American ‘voice-of-the-movement’ sister visited the museum with her daughters and found it to be most amazing! … She had never seen such a modern and exquisite tribute to the civil rights movement as that found in Atlanta.” Should we just say, “Thank you for funding this great entertainment”?

Question: Are we OK with the possible impact on the brand of museums and the deep social trust that they inspire when the museum brand is co-mingled with that of a commercial enterprise? Is there an argument that this process can have a positive impact on the corporation, making it more sensitive and dedicated to the public good?

Question: If we find advertorial content in a museum should we call this out? Should we seek to defend a museum’s content from undue influence by private or corporate funders? If so, how?

I think it is possible to build a behavioral practice of defense by using clearly stated and broadly agreed-upon mission and core values, if these are held in a position of authority and allowed to genuinely drive decisions. But how often is this the norm?

Question: Is the Center for Civil and Human Rights a museum? Their About Us page summarizes their mission this way: The Center for Civil and Human Rights in downtown Atlanta is an engaging cultural attraction that connects the American Civil Rights Movement to today’s Global Human Rights Movements. Our purpose is to create a safe space for visitors to explore the fundamental rights of all human beings so that they leave inspired and empowered to join the ongoing dialogue about human rights in their communities.

I inserted the Center for Civil and Human Rights into the brand of museums. I did so because it feels like a museum. It uses all the tropes and conventions of a museum. It may not call itself a museum, but what is a “cultural attraction” that leverages the potent brand of civil rights, the story of Martin Luther King Jr., and artifacts from the Morehouse College Martin Luther King Jr. Collection if not a museum in all but name?

Question: Are we all okay with a kind of strange reincarnation of “separate but equal” among museums, one in which institutions that are able to attract big money become dominant and controlling to such a degree that they can keep nearly all good things for themselves? Is this happening in Atlanta? Are the circumstances that have left the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site Visitor Center in sad disrepair—with no 21st century technology and no archives—unique to Atlanta? Or is this something that has been or is being repeated elsewhere?

I realize that my general line of inquiry leads to some complicated issues in which institutions have to balance their capacity to have a positive impact out in the world (often directly connected to the ability to raise money) and the integrity of their content. I know that content is subject to an array of influences and pressures of all kinds, including financial. I also know that nothing is ever free, and no content is ever pristine, but where is this line? Where should it be? Where is the line for your institution? How clearly have you drawn it and how do you defend it? Does the line move when the dollar figures grow large enough? I’m pretty sure that in most cases the answer is … yes.

Photos by the author

Ask for help.

We are kind, thorough and ready when you are. You just need to ask.