Post published in December, 2010

Architects fell in love with Flash. I think it gave them the kind of absolute design control that they generally expect from the world. The problem, of course, is that the Internet no longer loves Flash, and it seems architects are slowly coming to terms.

When Fast Company published “Why Can’t the World’s Best Architects Build Better Web Sites?” back in March 2010, it was a kind of an epiphany for me. I understood then what was going on with our architect clients. It was a feeling of, “Oh, now I get it, it’s not OUR architect clients. It’s architects in general.” And it’s something that’s perhaps fundamental to their nature. Flash was a near perfect tool for them—you could design then build something, and guess what, it looked and worked exactly as it was supposed to. Flash had clarity, precision, and dependability—everything you’d expect an architect to appreciate.

Flash had clarity, precision, and dependability—everything you’d expect an architect to appreciate.

The rest of the Internet that does not use Flash is a bit messier, less under control, and although the design controls for this more accessible and content-driven world have dramatically improved, they are still not able to replicate the smoothness and exactitude of Flash. In the 10 months since this article came out, some of those in the high-end architecture community have begun to make accommodations to the new reality, but many others are seemingly taking the position that they are above it all.

Around the time of the Fast Company article, we failed in a concerted effort to convince a client to develop their new website in PHP instead of Flash. We explained why it was a good idea, and we built a demo to show them. But the process ended with them rejecting the idea because of details like the kerning of a custom typeface that they insisted we use.

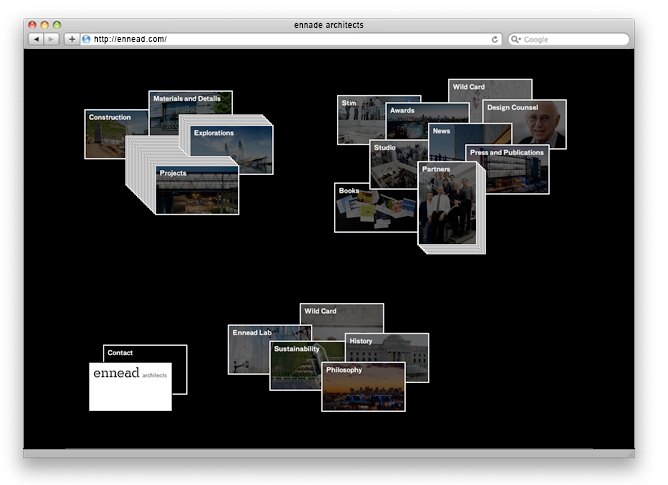

This control freakish tendency among architects is perhaps one reason why Flash websites like Ennead (built by Pentagram for the firm formerly known as Polshek Partnership) are the way they are. Given contemporary Internet standards of more open access to content, more standardized navigation, and focus on ease of use, this website is remarkable for its design hubris and seeming disregard for these factors. Despite this, the site has been strongly praised within the architecture community as “one of the better architect websites to come along in a while” by Architizer. For me though, this is a perfect example of what Alissa Walker describes as “gimmicky navigation using images and rollovers instead of simple, clickable text” and although all the project pages now have permalinks, only the first page of the entire site is indexed by the major search engines. Considering the stature of this firm, the website provides them with little in terms of online credibility.

There is a possible parallel between this attitude toward the architecture of a website in relation to its environment (in this case the web), and the tendency of some architects to build what they build regardless of the surroundings. Great architects are designers who have made a name for themselves by not following conventions. Why should their websites be any different? It would be interesting to see if there is any kind of correlation between the architect’s tendency to disregard—or conversely, pay close attention to—the surroundings/context of what they design and build, and the ease of use of their websites.

Ennead is certainly a kind of “statement” website that falls short of its potential in terms of usefulness. As a marker of its self-focus that it has only one page indexed by Google—same for Yahoo and Bing—so it is as if the whole structure they have built were buried underground, invisible to all the world until someone choses to step through the single doorway at the entrance.

Alexa’s traffic rank for the site is #3,731,791, which means it’s the three million, seven hundred thirty-one thousand, seven hundred and ninety-first most visited website in the Western world. So a lot of people who might otherwise be going in and looking around aren’t. They are missing the doorway as they pass by.

Great architects are designers who have made a name for themselves by not following conventions. Why should their websites be any different?

57 domains link to Ennead. This means that of all the websites in the world that talk about architecture, 57 have made a signpost that says you should go there. That is not that many. Of all the numbers I am taking note of here, this one is probably the most important, and for a company of this stature it should be more like 1,000 or preferably 5,000. But for that to happen, Ennead would have to be fully engaged with the online world. Their structure would need to be above ground with lots of ways in, lots of stuff to see, and lots of visible activity inside. What Flash and Pentagram have created for them instead is a kind of subterranean black box that only the initiated are asked to come in and see. And oh, by the way, if you do get in, you can look but don’t touch. Maybe this suits their business model. Maybe they are not hurting for new projects, so who am I to recommend that they do anything differently …?

I would though, like to compare Ennead with a website like Foster and Partners, where despite having an outdated design (referencing their 2010 website), the website content is fully accessible. The resulting numbers are an order of magnitude better than Ennead’s despite the latter’s website being much newer. (See Sir Norman Foster’s website stats below.)

The Foster and Partners website looks like it was developed a while ago, and this leads to another important point. The architects who acted on their compulsion to create something in Flash in the last few years were able to build very personalized and highly designed online expressions of themselves, but now they are having to pay the price for this choice both in terms of search, and in many cases, usability. (This is an entirely separate issue from the brand authority or appropriateness of the website designs themselves, but we’ll leave that for another post.)

The architects who acted on their compulsion to create something in Flash in the last few years were able to build very personalized and highly designed online expressions of themselves, but now they are having to pay the price for this choice both in terms of search, and in many cases, usability.

Limiting our focus strictly to some of the key criteria that represent online power (content, traffic and links) let’s look at the websites of all those who have been awarded the coveted Pritzker Architecture Prize. Bear in mind that one could well argue that receiving the Pritzker Prize may actually exempt these architects from needing to work on their online reputations at all, and this may in fact be why so many of them don’t even have websites.

For those that do, we have attempted to compare them on the bases of indexed content, traffic and links*. (In cases where there seems to be no official website, we have simply noted their name with no link.)

Note: This blog post was written in December 2010, two lifetimes ago in web time. So much of the information and the sites that these links lead to have subsequently changed, some dramatically.

2010 – Kazuyo Sejima + Ryue Nishizawa

pages: 1

rank: 2,241,733

links: 454

2009 – Peter Zumthor

2008 – Jean Nouvel

pages: 62

rank: 2,771,248

links: 278

2007 – Richard Rogers

pages: 4,850

rank: 3,455,001

links: 238

2006 – Paulo Mendes da Rocha

2005 – Thom Mayne

pages: 2

rank: 2,573,228

links: 640

or

pages: 832

rank: 1,195,672

links: 175

2004 – Zaha Hadid

pages: 289

rank: 248,435

links: 2,349

2003 – Jørn Utzon

pages: 822

rank: 26,582,285

links: 110

2002 – Glenn Murcutt

2001 – Jacques Herzog & Pierre de Meuron

2000 – Rem Koolhaas

pages: 1

rank: 2,251,776

links: 1,176

1999 – Norman Foster

pages: 1,060

rank: 186,187

links: 3,124

1999 – Renzo Piano

pages: 5

rank: 1,340,943

links: 323

1997 – Sverre Fehn (1924-2009)

1996 – José Rafael Moneo

1995 – Tadao Ando

1994 – Christian de Portzamparc

pages: 16

rank: 13,313,219

links: 10

1993 – Fumihiko Maki

pages: 155

rank: 1,615,560

links: 198

1992 – Alvaro Siza

1991 – Robert Venturi

pages: 1,240

rank: 3,971,887

links: 328

1990 – Aldo Rossi (1931-1997)

1989 – Frank Gehry

pages: 10

rank: 1,640,427

links: 586

1988- Gordon Bunshaft (1909-1990) & Oscar Niemeyer

1987 – Kenzo Tange (1913-2005)

1986 – Gottfried Böhm

1985 – Hans Hollein

pages: 1,080

rank: 23,301

links: 141

1984 – Richard Meier

pages: 69

rank: 1,030,879

links: 852

1983 – I. M. Pei

pages: 147

rank: 2,472,351

links: 389

1982 – Kevin Roche

pages: 165

rank: 12,568,365

links: 93

1981 – James Stirling (1926-1992)

1980 – Luis Barragán (1902-1988)

pages: 11

rank: 5,970,327

links: 142

1979 – Philip Johnson (1906-2005)

pages: 483

rank: 3,901,851

links: 98

Ask for help.

We are kind, thorough and ready when you are. You just need to ask.