In celebration of the Kyoto Journal’s issue 83 to which I contributed a small fragment of this story I here tell it in full. There is no branding, strategic or organizational alignment message, even at the end. It is just a story of foolish youth.

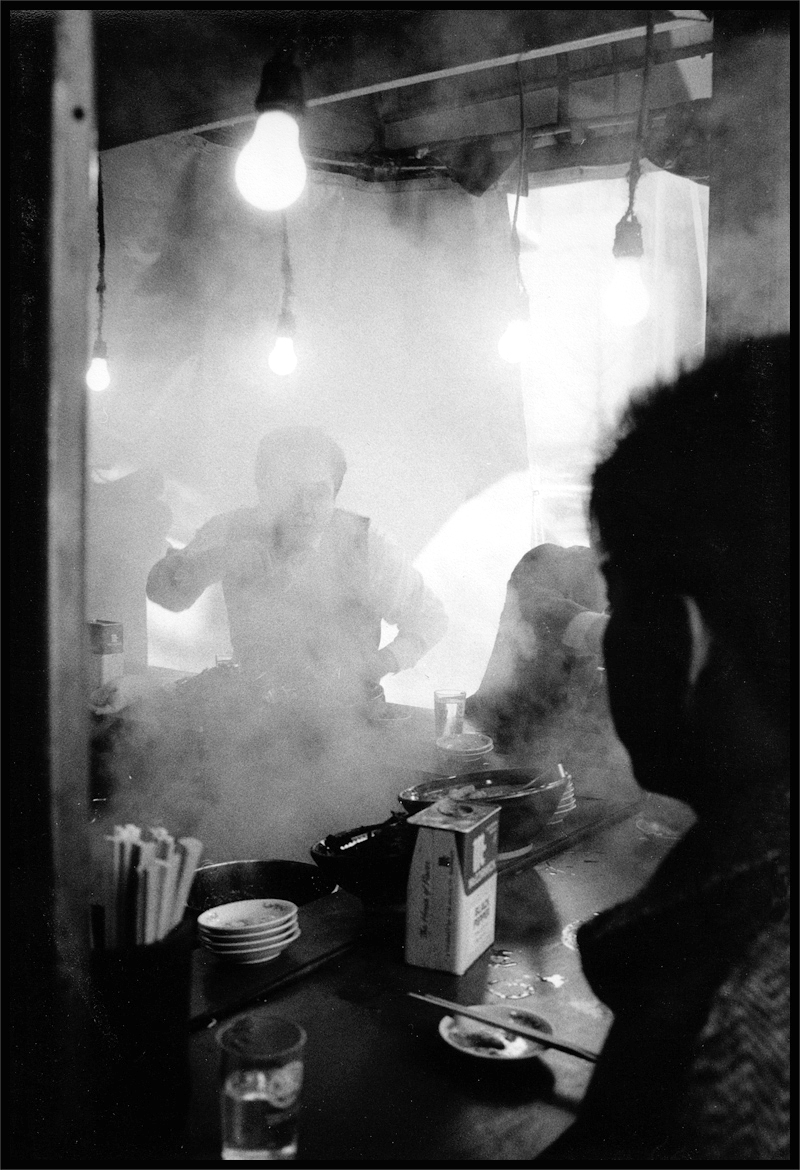

Putting on fat in Chengdu

Tom from the UK and I met over a pile of someone else’s food. We were both staying in a hostel that, for some reason, was underground and connected to a night club.

I had been away from my girlfriend back in Japan for a month and a half at that point. I was in Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan Province adjacent to Tibet. Food and adventure with amusing strangers was a great consolation for loneliness.

The dazzling display of food laid out before us belonged to an out-of-town businessman and his friend. They weren’t really eating any of it, and Tom and I both volunteered to help out. It seemed that every time we ate something the businessman would simply order more. It made no sense to me at the time, but Tom and I were happy to tag along. For a short while Tom and I become part of this businessman’s unofficial entourage.

This was spring of 1986. The new rich were visible in China after eight years of “It doesn’t matter if a cat is black or white, so long as it catches mice.” type economic reforms under Deng Xiaoping, and some, like our new friend, were finding their way in this new wealth by overcompensating for their own experiences of food scarcity in previous decades. The ostentatious waste we enjoyed for a few days in Chengdu was, I think, our benefactor’s proof to himself that a new and fundamentally different China had arrived. He was seeking to bury his memory of the famines of the Great Leap Forward in a veritable mountain of food. Two scavenging foreigners may have completed the scene.

My own upbringing by depression-era parents made it nearly impossible for me to sit by and do nothing in the face of food waste. I cannot speak for Tom’s motivations.

The fundamentality of food infuses it with great power. It literally shapes us. Natural, universal, and mostly routine, the act of eating hardly attracts special attention under normal circumstances, but travel—especially solo travel in unfamiliar cultural contexts—sometimes brings this simple, necessary act into sharp focus.

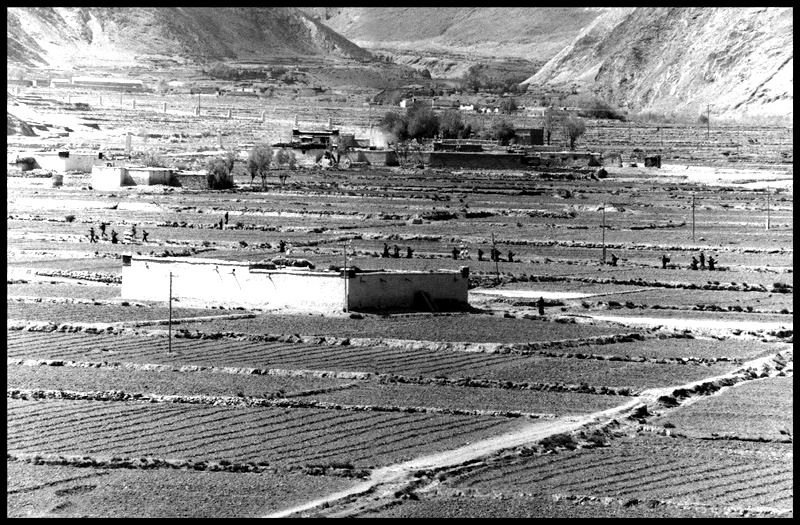

Tibet

Our businessman friend now gone, it was time for Tom and me to carry on with our respective solo journeys. He was headed to Urumuqi. I never saw him again. Tom, I hope you are well.

On a whim I decided to fly over the mountains into Tibet. By late afternoon the day after we said goodbye, I was stepping off a plane into very thin air on the outskirts of Lhasa.

Tibet was alive with hope and small-scale commerce. China had liberalized, the nightmarish destruction of the Cultural Revolution was a decade in the past, and it was still more than a year before clashes with government authority would result in terrible violence there. This particular moment was a kind of happy interlude. I am lucky to have experienced it, because the Lhasa I saw is no more. This is the way of all things I know, but my Lhasa was a truly magical place. The central market was full of handcrafted wares and hopeful, almost giddy people who were so full of warm welcome that it was almost shocking. It was as if all the sour faces and obstructions that had characterized so much of my travels in China had been turned inside out. Here existed an alternate universe where people were suddenly happy to be alive. I was exhilarated.

I was also having difficulty finding food of the sort I could eat. Having lived in Asia for two years at that point, I considered myself pretty flexible. While in China proper I had been able to read menus and write things down—in my Japanese version of Chinese—for servers to interpret. Here we were all left guessing.

I particularly remember a meal the day I arrived. It was stir-fried chunks of yak fat (no meat that I can recall) and black squiggly wood ear mushrooms. I ate it all. I was not in a financial or behavioral position not to, but I remember that it was a challenge. It was probably also exactly what I needed, and it may have helped dispel my altitude headache.

There were other westerners collected in Lhasa at the time, more in fact than anywhere else I had been. I met a woman from Yale who was studying in China proper, and referred to Lhasa as her “escape.” She came whenever she could. Because of this traffic of foreigners, there were some local attempts by entrepreneurial Tibetans to improvise western foods. There were “yak burgers” for example, cooked by hand on a makeshift open fire. I had one and it was grossly undercooked. I did not get sick, but I did refrain thereafter.

As is often the way of unscheduled trips while alone in strange places, interesting things do happen. I soon found myself teamed up with a collection of ten Japanese who were also in their early 20s and who had arranged to rent a bus and driver for a week of mobile exploring in the vicinity of Lhasa.

This was a fantastic excursion, and a great relief for me because now I shared not only a local guide, but the group now made food and other decisions by consensus. It was effortless. I cannot remember anything we ate that entire part of the trip. I had restored ordinary to the food aspect of my journey. It seems that only the extraordinary—one way or the other—has the power to stick in memory when it’s a matter of what is essentially a mandated routine.

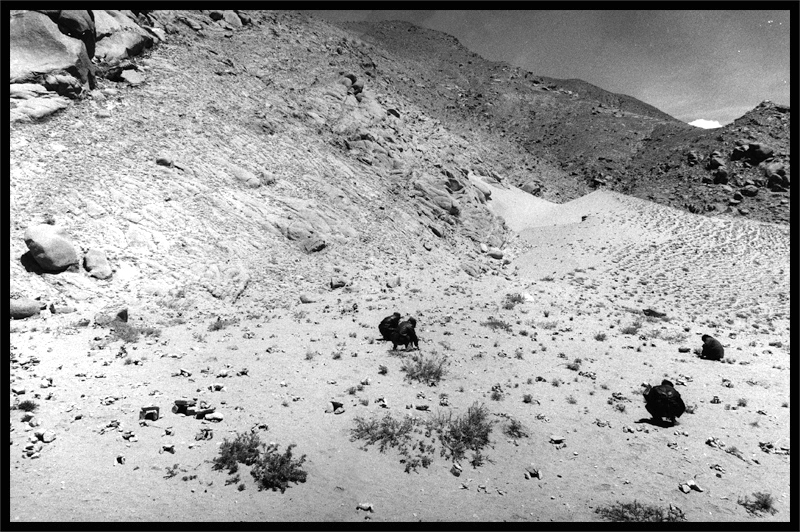

The standout on that excursion was certainly a sky burial (don’t look at the pictures) that we happened upon. We hiked up a mountain to see its conclusion. The monks had completely cut up a recently deceased man. They were almost done feeding his temporal remains to great scavenger birds, birds of prey, and other natural recyclers. I don’t remember if this did or did not put me off eating for any interval.

Also during this leg of our trip the Chernobyl nuclear disaster happened in the Ukraine, and thanks to the jet stream, we were gifted with a little extra radiation that week as we traversed the astounding landscapes of south central Tibet.

When we returned to Lhasa and its relatively low altitude (for Tibet) of 11,975 feet, some of our group set out for Mount Everest base camp (16,900 feet) and invited me to go. Given what happened to me next I cannot say whether it would have been better for me to have gone that way, but I imagine it would have been if only for the fact that I would not have been alone. I probably would have also been shielded from eating anything stupid. Based on an account of their trip I obtained later by chance, it was a great adventure that included the base camp and an excursion on through much of India. That would have been a trip well suited to my then-self: 21, healthy, and full of hubris.

Instead though, I decided to return to Japan. Just having spent an extended period of time with a group of young Japanese made me homesick for my life back in Japan, and I especially missed my girlfriend. I had been away for two months at that point. I said goodbye to everyone, bought an intricate and beautiful hand-crafted silver jewelry box from a seller in the circular central market of Lhasa, packed it up with the rest of my gear, and headed for the bus depot to buy passage out of Tibet.

Instead though, I decided to return to Japan. Just having spent an extended period of time with a group of young Japanese made me homesick for my life back in Japan, and I especially missed my girlfriend. I had been away for two months at that point. I said goodbye to everyone, bought an intricate and beautiful hand-crafted silver jewelry box from a seller in the circular central market of Lhasa, packed it up with the rest of my gear, and headed for the bus depot to buy passage out of Tibet.

The exit plan

I chose to leave Tibet by bus via the northern route about which I knew nothing, and in order to save money, I also decided to take the “people’s bus” instead of the much nicer one intended for foreigners. This took extra effort because a non-Chinese could not buy tickets for the lousy buses. Strangely however, if you had a ticket, it was no problem to ride one. I convinced a stranger to get a ticket for me, and I watched as the nice bus loaded up with businessmen and foreigners.

Then I saw the chickens and goats being loaded onto my bus, and I realized that it was going to be full, and also that it was deficient in more than just space. It was missing some windows. This bus was going to be my home for what turned out to be a few days in the midst of some of the most desolate and forbidding terrain on earth. The highest of the mountain passes that this rickety bus would have to traverse without windows or heat—me and a few other unlucky passengers inside—was the TangGuLa Pass which is well over 17,000 feet. For perspective, the highest mountain in the contiguous United States is 14,505 feet. You cannot practice being up this high, and please note that I grew up in Florida all of eight feet above sea level.

As the bus headed north, out over the plateau of central Tibet, I witnessed and photographed some absolutely spectacular landscapes in DamXung, and I remember the bus driver stopping the first time and seeing everyone scrambling off the bus to spread out over the open rocky landscape in order to pee and whatever else. The fact that the driver had waited so long before stopping was, I would later realize, a reflection of his somewhat sadistic personality.

We stopped to eat late in the day. In this lonely town there was one place serving food to outsiders, and I had lukewarm tofu soup with lots of ginger. It was awful and I ate it all. The memory of that meal, my last meal for nearly two weeks, would put me off ginger for more than twenty years.

Over the next few hours I became deathly ill. I later found out that I had contracted dysentery AND this was compounded by, duh, altitude sickness. After leaving this town, equipped with my gift of some pretty virulent bacteria, our bus proceeded to break down on some desolate and windswept portion of what was now a snow-covered desert. I proceeded to severe diarrhea. Thinking back, I’m glad they did not throw me out of the bus to die in that frozen wasteland. The bus had emptied a bit so I had a seat to myself. Maybe that was enough distance from my quiet suffering. Maybe dead passengers were not much of a resume builder. The bus was eventually restored enough to keep moving, and because it did not really stop at all after that, I took to shitting in my sleeping bag.

I commemorated the two-inch accumulation of snow from the frozen desert that collected on the seat back in front of me with a photograph (which I was unable to find in my negatives despite a concerted effort). Being deathly ill did not at any point stop me from taking photographs. By the afternoon of the third day, having spent some extremely unpleasant quiet time at altitudes over 17,000 feet, we descended into the Qaidam Basin, and approached the edge—or perhaps the dirty fingernail—of Chinese civilization: Golmud. Golmud was the then-terminus of the rail line, and the path for me to Shanghai, my ship to Japan, and the waiting, warm, and lonely arms of my girlfriend.

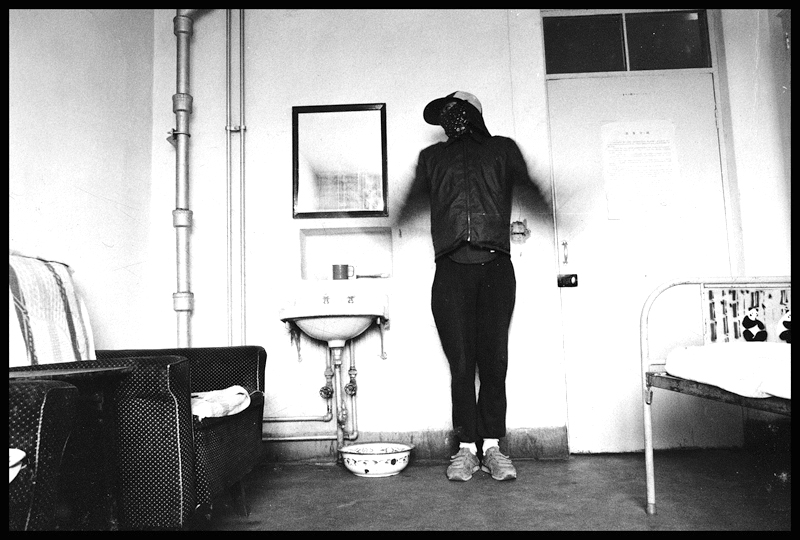

Holed up in Golmud

As we approached but did not actually enter Golmud, the bus driver stopped the bus and opened the door. A heated argument ensued between the other passengers and the driver apparently over why we were not being taken into town. The passengers eventually lost the argument. Everyone started filing out of the bus and walking down the road ahead of the bus. This meant I too was going to have to get out and walk. I did not feel like I could walk, and I had in tow all of my stuff from three months of travels (including an intricate silver jewelry case for my girlfriend), and a shit-filled sleeping bag.

Somehow I did manage to walk what seemed like 1,000 miles into town. About 15 minutes after the bus was fully unloaded, he drove past, rumbling down the same road on into the town, bus empty. I’ve never quite figured that one out, but it certainly sucked.

So, rather inauspiciously, I arrived in Golmud. Immediately ahead of me was a 28-hour train ride to Langzhou, and another 24-hour train ride from there to Shanghai, a 48-hour boat trip to Kobe, and then a short jog to my home and girlfriend back in Kyoto. While this was technically possible in 5 days, this trip ended up taking me another month.

Today one of the most polluted industrial cities on the planet, Golmud was then the Chinese equivalent of a cow town. It was only recognized as a city in 1980. It did, fortunately for me, have a small medical clinic, at which a stout nurse gave me a shot in the butt, some yeast pills, and a note that described my illness so that I could have a better chance of obtaining a sleeping berth on the train to Langzhou. I paid the equivalent of $1.50 for what was probably life-saving assistance, and I was instructed to stay hydrated and get bed rest.

I remained in bed in a small room in a Golmud hostel for a week. I could hold down water, fortunately, but nothing else. My routine consisted of sleeping, fetching boiled water from a boiler near my room, and laying in bed looking at the ceiling.

At a certain point I realized that I could die here in the middle of nowhere, and I remember sitting on some rocks in front of the hostel, the sun beating gray dust all around me, and deciding that I had to go. I had to strike out for home or I was literally never going to leave.

I collected my things, walked to the train station and bought a “hard seat” ticket planning to upgrade on the train to a sleeping berth. The hard seats were cheap, but descriptively literal. It was not a good plan for me to try to sit in a hard seat for the next 28 hours, but it was what I ended up with.

I boarded, and after some delirium sitting upright, I sought out the conductor and showed him the note requesting an upgrade to a hard sleeping berth. He agreed and I remember that when I got to the sleeper car it was empty. I slept. I slept as we passed Tuosu and Gahai lakes and I dreamt of Lop Nur. I awoke, and saw the blue surface of Qinghai Lake. I was hungry for the first time in two weeks. My good sense, however, had not returned with my appetite. At the next short station stop I bought, of all things, a large sack of roasted peanuts in the shells. This was probably a nostalgic purchase as I had always loved roasted peanuts.

I ate one. It was good. I ate another, really good. I began devouring peanuts. My next memory is of lying down between two cars of the train as it rumbled over the tracks and watching my peanut-laced vomit splatter the dusty soil moving in a blur below. When I finished, I still felt better than I had in weeks.

Yogurt in Langzhou

I waited before I tried to eat again. Arriving in Langzhou I had difficulty finding accommodation—I remember my stuff being unimaginably heavy as I walked from place to place repeatedly asking and being refused because they had not been licensed to accommodate foreigners. I did not realize at the time that I was in a happy place.

My next train, the one that would get me to Shanghai and both friends and a familiar version of civilization, was to depart the following day at around noon.

I vividly remember the beautiful blue-skied morning in Langzhou that day. I ventured out in pursuit of something to eat. I was hungry and cautious after my peanut experience the day before. I found a street vendor selling yogurt in paper cups. I purchased one and slowly ate it. It was wonderful. It was slightly sweetened whole yogurt with a thick layer of fat on top.

That particular paper cup of yogurt and the ginger-laced tofu from two weeks before make up the food frame for my ordeal. The meal with excessive ginger that put me down meant I struggled with ginger for nearly 20 years. That morning’s yogurt in Langzhou, however set the standard for what yogurt aught to be. I have never since been satisfied by any yogurt bereft of its fat, and I have never since tasted any yogurt as good (it may have been fresh, unpasteurized goat milk yogurt).

The yogurt stayed put. I felt ok for the first time in two weeks. After a pause I had another cup, and another, and another. I ate nothing but yogurt from then until I had traveled too far east to find any. It basically vanished after we passed Xi’an, a city I would not get the chance to actually see until ten years later.

I cannot remember if I ate anything on the last leg of my trip to Shanghai, but I think I did not. It’s interesting how food is either utterly memorable or utterly unrememberable. There is almost nothing in between. And the food that is rememberable is so for its extreme rarity, unusualness, or profound unpleasantness. I guess the amygdala is at work here too, locking in those food memories that are accompanied with emotional content.

These two food experiences that bracket my near death at age 21. Both had emotional content.

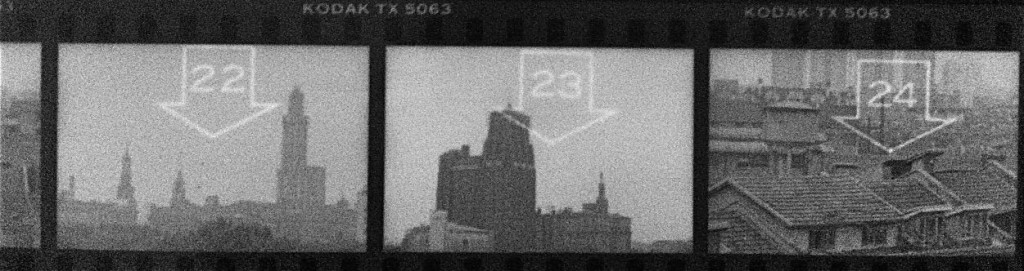

Glorious Shanghai

I lodged in Shanghai (at sea level) for nearly two weeks to recuperate. Shanghai in 1986 had no skyscrapers. Pudong was nothing but a spot to put up billboards for Japanese manufacturers like Sanyo. (This before and after captures it pretty well.) Bicycles were everywhere and the Mao suit was still common, broken only occasionally by a brightly colored dress. I was staying as a guest of a Japanese businessman whose son was a good friend back in Japan. This put me on the 6th floor of a very nice hotel right on the Bund. I could eat in the hotel, and along nearby Nanjing Road there was easy access to the best Shanghai had to offer. I was happy to recuperate here, and I will always have a soft spot in my heart for Shanghai.

I remember a dinner given by my host intended to showcase the glories of Shanghai-style seafood. I also remember a quest for “comfort food” that I undertook right after arriving back in Shanghai.

I remember a dinner given by my host intended to showcase the glories of Shanghai-style seafood. I also remember a quest for “comfort food” that I undertook right after arriving back in Shanghai.

I had a deep irrational craving for, of all things, sweet and sour pork. The odd thing is that I don’t really eat sweet and sour pork, so exactly how this became, at that moment, a comfort food for me I am quite unsure. Perhaps there is a clue in the time I became ill in Bangkok and had an insatiable craving for a bologna sandwich—a particular kind of bologna sandwich, a kind I’m sure we never would have had at home—and yet there it was drawing me like a moth to a light.

Could that sandwich have been something I once had at a friend’s house that had fallen into some unconscious association with normalcy, with a state of grace that sometimes fills a memory from youth? Was this association drawn out somehow in a moment of weakness? Could I have once had and greatly enjoyed sweet and sour pork, and just let that memory recede into the myriad of other non-pivotal food moments that make up our real lives? Was this only retrieved by chance at that particular moment in Shanghai? The power of the desire was strong enough to seem physiological—an intense craving. Maybe at that moment I needed protein, and that was what my mind/body landed on as its best incarnation.

It’s not a Shanghai specialty and there was no internet to look up where I could find such a meal. I’m not sure I even knew what it was called in Chinese, so I explained as best I could to my Japanese host, and he directed me out to some hotel along Nanjing Road. I found what I was looking for. That meal of sweet and sour pork at some overpriced restaurant in the late spring of 1986 was deeply satisfying.

I was ready to board the Ganjin and take the seaborne last leg of my journey back to see my girlfriend.

Food flight accomplished

I remember nothing of the forty-eight hours at sea, but my food flight from China was nearly done, and I vividly remember the euphoric feeling of being back on land in Japan. I felt like I was master of the universe.

I beelined to what was then one of my go-to eateries, Gyoza no Osho. (Let’s call it Dumpling King. The resemblance to Burger King is intentional. But give it a strong Chinese theme and replace hamburgers with pan-fried dumplings.) This Kyoto-based chain was cheap, tasty, and everywhere. One of the aspects of its Chinese theme was katakana versions of Chinese names for each item printed on the menu. The servers would shout this “Japanified” Chinese version of your order.

I waltzed into a Gyoza no Osho in Osaka and ordered off the menu in actual Chinese. I was not understood.

The meal was as expected, and I gradually began to creep back into a normal relationship with reality, but not before I called my girlfriend from a pay phone, spoke to her for the first time in three months, and headed to her house anticipating a glorious, long-awaited, and hard-won reunion.

Reunion

When I got to the outskirts of Kyoto and her mother let me in, I had to go to the bathroom rather urgently.

Please note that traditional Japanese houses like this one have various slippers appropriate for use in different rooms. One pair for the bathroom, another for the kitchen, and no slippers for tatami rooms.

I came out of the bathroom and walked into the living room with its fresh green tatami and my girlfriend’s mother rendered speechless in her mortification, gestured mostly at my feet and grunted as if in pain. It was at this moment that I saw my girlfriend, the inspiration for my hasty and experience-laden return, and realized that I was still wearing the bathroom slippers.

My girlfriend seemed rather withdrawn considering the circumstance. We excused ourselves from her mother after the slippers were restored to order. And we entered into a kind of surreal emotional dance of a conversation. She was happy to see me but had news.

I gave her my gift preserved from Tibet. She accepted. Then came the news: In my absence she had gotten back together with her former boyfriend. They were now engaged to be married. He was waiting in the other room. Would I like to meet him?

… Um. No thank you.

I went back to my favorite Gyoza no Osho, in Yamashina nearest my tiny four and a half mat apartment. I ordered a big bowl of ramen. This time, hubris gone, I ordered in Japanese.

Coda

I saw her only once after that, a few years later. I cannot remember exactly how we bumped into each other, but it was probably at a calligraphy exhibition as we had met studying under the same master calligrapher. She was still married, but the house—the beautiful Japanese-style house she had lived in with her parents and then with her husband—was gone. It had burned to the ground in a terrible fire.

“What of the silver jewelry case from Tibet?” I asked, unthinkingly.

“Gone,” she said. I thought of Lhasa, of the market, of the feeling of hope and aspiration that filled all of those I had encountered there.

“I’m very sorry,” I remember saying, and I was—for her, for me, and for the dashed hope that a small, lovingly made box might be thought to contain.

All photos by the author

Ask for help.

We are kind, thorough and ready when you are. You just need to ask.