I flew out to California for Museum Camp last week on the power of a hunch—if Nina Simon was doing it, then I would learn a lot. That was a pretty good hunch.

What was Museum Camp 2014?

For the uninitiated: Museum Camp (hosted by the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History and Fractured Atlas) is a unique professional development program that gathers 100 diverse participants from a wide range of academic and professional disciplines for four days in an effort to stimulate hands-on creative and collaborative learning around a particular theme.

This year’s focus was social impact assessmenta, or measuring the effects that a program (or a social gathering space) has on a community. We were split into small groups (my five-member team chose the moniker Team Secret Sauce) and each selected a different program, event or institution in Santa Cruz to assess for its social impact, through any means we could so quickly devise. For those who might question the value of such an exercise, let me count the ways that this process led me to deeper insights and new knowledge.

Nothing like a good summer camr experience to expand my little mind …

Nothing like a good summer camr experience to expand my little mind …

If you are unfamiliar with the Santa Cruz Museum of Art and History, please look up its Executive Director Nina Simon, author of the wonderful Museum 2.0 blog and also The Participatory Museum.

Interface matters.

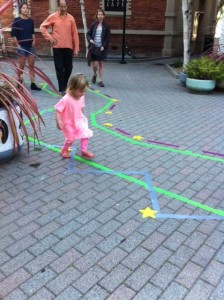

1) One project at camp got an excellent numerical response by taping the sidewalk. This was reinforcement of the idea that you should always pay close attention to the tactical user-level interface. In this case, note that people tend to look down as they walk. This behavior makes the sidewalk an interface worth paying attention to. As an interface, it has the further advantage of little density—not much else is going on, so whatever is there has little competition for message delivery.

1) One project at camp got an excellent numerical response by taping the sidewalk. This was reinforcement of the idea that you should always pay close attention to the tactical user-level interface. In this case, note that people tend to look down as they walk. This behavior makes the sidewalk an interface worth paying attention to. As an interface, it has the further advantage of little density—not much else is going on, so whatever is there has little competition for message delivery.

2) On the flip side of both the tactical user-level interface and the density issue, our own group at first thought we could use pink buttons mounted on our chests to prompt spontaneous responses from passersby. This did not work for various reasons having a lot to do with the tactical user-level interface: We were operating in an environment where buttons are not uncommon and there is no preexisting behavior that calls for strangers to see a button and because of it strike up a conversation with the wearer. So the button as a prompt may only work as a “third question”—something that is likely to come up naturally only in the context of an already initiated interaction of some kind, and even then, not as the first response, but as a later response. So, an initial response might be drawn out through a question like, “Can I get directions to the theater?” A second question might be an extension of the conversation to a second topic such as, “Is it always this nice in Santa Cruz?” After which the person heretofore answering questions might be ready to respond to the prompt because it provides a natural question to ask in reciprocation to the ones he/she has already been asked. It thus becomes the third question.

2) On the flip side of both the tactical user-level interface and the density issue, our own group at first thought we could use pink buttons mounted on our chests to prompt spontaneous responses from passersby. This did not work for various reasons having a lot to do with the tactical user-level interface: We were operating in an environment where buttons are not uncommon and there is no preexisting behavior that calls for strangers to see a button and because of it strike up a conversation with the wearer. So the button as a prompt may only work as a “third question”—something that is likely to come up naturally only in the context of an already initiated interaction of some kind, and even then, not as the first response, but as a later response. So, an initial response might be drawn out through a question like, “Can I get directions to the theater?” A second question might be an extension of the conversation to a second topic such as, “Is it always this nice in Santa Cruz?” After which the person heretofore answering questions might be ready to respond to the prompt because it provides a natural question to ask in reciprocation to the ones he/she has already been asked. It thus becomes the third question.

3) Simple and easy to use interfaces are better. Duh, but we ALL need CONSTANT reminders of this. Rudimentary “sticker” interfaces, such as the one shown above right, worked pretty well, even for those who vocalized they they never take surveys.

Use simple mechanics.

4) One of the most productive experiments, in terms of its data yield as well as the number of additional questions it spawned, had extremely simple game-like mechanics: Wear a hat, write your name on it and pass it along for good Karma.

4) One of the most productive experiments, in terms of its data yield as well as the number of additional questions it spawned, had extremely simple game-like mechanics: Wear a hat, write your name on it and pass it along for good Karma.

5) Another group got useful data by creating an analog version of a touch interface, noting where people touched on a printed mood circumplex. It’s a great example of how formal constraints (such as little time and no available technology in this case) are great stimulants for creativity.

Work in your sleep.

6) Despite a relative lack of sleep, camp allowed me to test some of my own theories on how sleeping can contribute to the creative process. Others at camp reported some of the same positive effects of using sleep to filter complexity. I ended up describing how I do this to Team Secret Sauce. I was able to articulate a kind of procedure: a) Think about the problem you are working on before you go to bed. b) Imagine yourself putting the problem on a shelf just before you go to sleep. c) The moment you wake up, remember to retrieve the problem from the shelf, and inspect it again. d) As you do this take note of any new observations or insights. Writing these observations down—or drawing them—is a reliable tool for distilling ideas that were not fully processed the day before. I have used this tool for many years, but Museum Camp gave me the opportunity to describe it in enough detail to clarify and illustrate what I had been doing for myself intuitively.

Others at camp reported some of the same positive effects of using sleep to filter complexity.

This extraction of a specific process was a byproduct of the camp setting in which we were working in small groups as a team over a period of days. This multi-day introspection and repeated and sustained discussion on a consistent subset of topics also had the effect of helping me to codify some other devices that I have been using in my work, but had never felt obliged or been given the opportunity to fully explain.

Make it teachable.

7) I practiced, but had never explained—until it came up in one of our group discussions—that in an interview, it is very useful to repeat the most important questions in different ways so that you are able to get multiple responses and thus a more complete answer. I have always done this, but camp made me consciously expose my practice, and thus make it teachable.

You can always make it better (persona interviews).

8) Camp also made me explain our persona interview process repeatedly to some very smart people who already had some knowledge of standard research methods. In the act of not becoming bored with my own explanations, and in recognizing I could skip past the basics, I explained our persona interviews in ways I had never done before, and these repeated attempts to be precise in my explanations actually clarified one of my operating theories.

8) Camp also made me explain our persona interview process repeatedly to some very smart people who already had some knowledge of standard research methods. In the act of not becoming bored with my own explanations, and in recognizing I could skip past the basics, I explained our persona interviews in ways I had never done before, and these repeated attempts to be precise in my explanations actually clarified one of my operating theories.

I know that the persona interviews as we have structured them work. Museum Camp forced me to focus on explaining why they work. So here you go: These interviews serve to circumvent the strong tendency of any individual to unintentionally construct a rationale for their behavior, and to trust their own intention. This intention is formed based on a self-image that is idealized or distorted by the natural shortcomings of self-perception, and so even the most open and honest person will tell you about their intentions in ways that are not fully indicative of likely behaviors. This is worthy of an entire post, but, in essence, I was able to synthesize my theory of the mind (as it pertains to marketing) with the general and often remarkable serviceability of our persona interview tools. Thank you Museum Camp.

Even the most open and honest person will tell you about their intentions in ways that are not fully indicative of likely behaviors.

9) The process of intensive explaining also clarified for me why our “guilty pleasures” question from early in the interview is such a good indicator of an impending persona interview failure. Failure in this context is the inability to get past the interviewee’s own self-image and obtain genuine emotional factors that are likely to underlie behavior. A failed interview does not successfully traverse this gap between intention—protected by self image—on the one hand, and actual drivers of behavior on the other.

10) It is possible that our interview failure rate is even higher than we currently suspect. We estimate it at about one in eight, but thanks to Museum Camp I now have a much clearer theoretical metric with which to asses any particular interview’s viability, and I could even insert additional tests of this to better determine which interviews we should throw out.

I still hate focus groups, but …

11) I have been very clear about why I do not like focus groups. I see them as exceedingly poor indicators of actual consumer behavior, but Museum Camp opened my eyes to their usefulness in other, more circumscribed contexts, such as facilitated storytelling. Check.

Inquiry is stimulus.

12) Inquiry (surveys, interviews of any kind, or questions or prompts) is stimulus. You (the inquirer or inquiry designer) are creating time and context to explore emotions or thoughts that may have been left unaddressed otherwise. This pushes hard on the two extremes of research—the more purely observational or data collection driven kind, and the intensely invasive kind (like ours). It’s an argument for mixed methods certainly, but also for strategy: What really is my question? How good a question is that? How hard can I fight to disprove my hypotheses or undermine my desire to support a particular outcome?

12) Inquiry (surveys, interviews of any kind, or questions or prompts) is stimulus. You (the inquirer or inquiry designer) are creating time and context to explore emotions or thoughts that may have been left unaddressed otherwise. This pushes hard on the two extremes of research—the more purely observational or data collection driven kind, and the intensely invasive kind (like ours). It’s an argument for mixed methods certainly, but also for strategy: What really is my question? How good a question is that? How hard can I fight to disprove my hypotheses or undermine my desire to support a particular outcome?

13) Social sciences and the kind of research we were experimenting with in Museum Camp—and that we use in our regular work—is always going to be dense with variables. It’s daunting, and I’m afraid it will never be precise in the way the physical sciences can be, but I’m really ok with that. When approached with eyes open and in the full spirit of inquiry, it can certainly be very useful and actually a whole hell of a lot of fun. Museum Camp reinforced for me how the scientific process is both hard work and fun. (Now I’ve just used fun twice in a paragraph about social science. I detect the influence of Nina here.)

Well, there are at minimum 100 more things I learned or improved in these 4 days, but I will now gradually stop.

Everyone has something valuable to teach, be it through the answers they give, or even better, the questions they ask.

14) In one of many stimulating conversations I had at camp, this question was posed to me by the indomitable Barbara Schaffer Bacon, “Is all your work about communication?”

My answer was immediate and I still think pretty good: “Yes, if you don’t have that figured out for your organization what do you have?” Social impact assessment is much more deeply connected to my work than I ever thought possible. I should know better than to be surprised to find a close connection between such things.

My bottom line takeaway from Museum Camp 2014 is that everyone has something valuable to teach, be it through the answers they give, or even better, the questions they ask.

What’s the secret sauce?

A very hearty thank you to all the other members of Team Secret Sauce: Elise Granata (our native guide to Santa Cruz), Becca Lynch, Ebony McKinney and Lisa Niedermeyer. You were all absolutely great … and EVERYONE else who attended and who made the effort to ask (including Paul Harder our line coach). I think we are all better for having met, and even though it was cheating the way we got to know Santa Cruz—through four days of research into 20 different aspects of the community. What a great place! Thank you Santa Cruz.

Video: Museum Camp’s Team Secret Sauce conducts an interview in front of the Del Mar Theater on Pacific Avenue in Santa Cruz.

Photo credits in order of appearance: Author; Santa Cruz MAH; Abbott Square (Team Labyrinth), One Minute Art Project: Fast, Fun, Free, and Easy, Karma Hat, Del Mar Cinema and Civic Pride in Santa Cruz x2

Related posts from campers:

Nina Simon’s MuseumCamp 2014: Experiments in Social Impact Assessment and Facilitating Creative Learning (for Professionals): More Notes on MuseumCamp

Katherine Gressel’s How I spent my summer vacations: Reflections on two years of “Museum Camp”

Joyce Kwon’s Takeaways from MuseumCamp

Jessica Fuentes’ Camp and Community

Alice Briggs’ Santa Cruz MuseumCamp 2014

Margy Waller’s Creative Connections

Becca Lynch’s Becca’s Santa Cruz Action Research Adventure: MuseumCamp 2014

Thanks so much for participating, learning, and sharing, James–I know I learned a lot from you.

I was so glad to see #6 on here (about sleep). One of the reasons we do this weird format where there are two full days and two half days is so there is as much opportunity as possible to sleep on something and refresh the following day. I especially find that about the first day (and think about this a lot in a consulting context). It is my suspicion that a one-day workshop spread over two days will always be more effective than putting it all on the same day, even with the same number of hours of content sharing. There’s a sense that anything that exists within a single day can wash over you and disappear. A night in the middle helps you come back in the morning on your own terms to make it your own.

Nina, I think you make a very important clarification. I was not thinking of this in terms of internalization, but that is certainly what is going on. In effect, you are creating an environment for learning that is designed to remedy the “wash over” effect that inevitably characterizes most, if not all, conferences. This triggers a whole collection of thoughts.

Vive la révolution!

Nina, that “collection of thoughts” is now a new post. Museum Camp gets a well deserved twofer.

See “Museum Camp: Can you take it with you?“

Like the taped sidewalk exercise, but wanted to hear more from the outcomes. It’s useful to hear the utility of the reframed question, since people take in information so differently, and also constantly waver in attention. Bet it was a fun group.

Kathleen, There is some more information on this and the other group projects here: http://camp.santacruzmah.org/abbott-square-team-labyrinth/

James,

I totally agree that communication is the primary source through which both the giver and the receiver are able to better glean from an experience resulting in clearer connections. I sure would have enjoyed a couple good nights rest as well. Thanks for sharing what appears to have been an amazing museum camp! The outcome link was truly helpful.