With March marking one year since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic here in the United States, anticipation over the full roll-out of the vaccine is high as the country anxiously awaits the end of the pandemic. An inescapable subject of public health messaging, it’s likely that everyone has some kind of opinion on the vaccine, from the state of the roll-out plan to the vaccine itself.

National polls conducted in December 2020 found that about 68% of Americans intended to receive a COVID-19 vaccine, though only 49.1% were “absolutely certain” or “very likely” to get vaccinated. In contrast, medical experts have estimated that achieving herd immunity (and effectively ending the pandemic) would require between 70 to 90% of the population to be vaccinated or infected. This gap in numbers has prompted serious concerns around how the American public can be convinced to get the vaccine.

As in healthcare marketing, encouraging a specific health-related behavior requires a deep understanding of how people behave and change, and how they respond to public health messaging. In light of the current reality regarding vaccinations, we pose the question: how can we effectively encourage changes in public health behavior?

The stages of behavior change

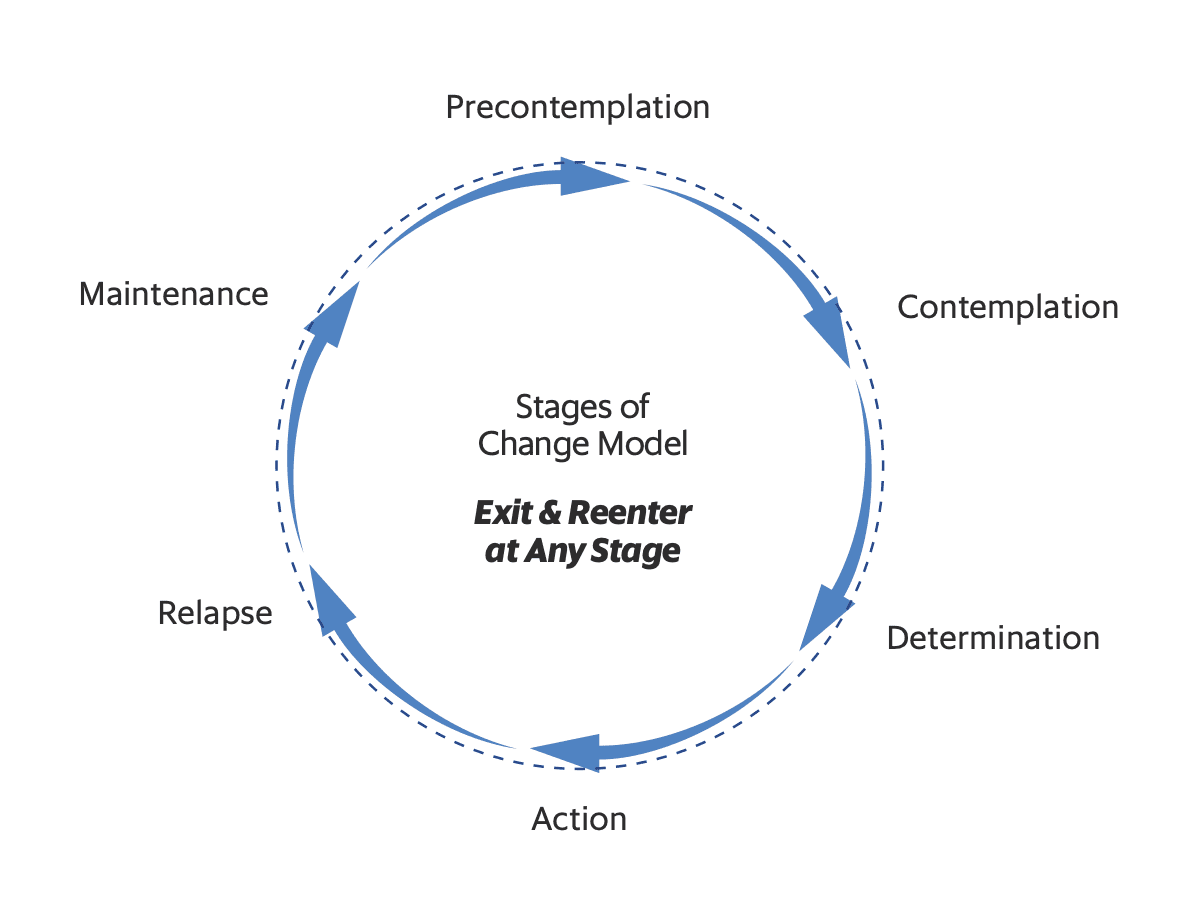

In order to encourage a change in behavior, there needs to be an understanding of the process of behavior change. For this, we can look to the transtheoretical model, which outlines the stages of readiness that individuals go through as they make decisions to change their behavior.

The model is rooted in the acknowledgment that most individuals go through several phases before they can commit to a behavior change. For example, if someone was unaware that they needed to change, they would have to first become aware of that fact, then move forward to actually consider it, and so on. By knowing what stage someone is in, we can better design programs and campaigns that will actually encourage them to advance through the stages and make the desired behavior change.

The transtheoretical model acts as a central guideline to positive health behavior changes. Movement through these stages often occurs cyclically, because many individuals must make several attempts to change their behavior before they meet their goals and move to the next stage.

Because the model is cyclical, there is no concrete “starting” stage. While efforts to change behavior right at the start of the pandemic would have had to reach people in the Precontemplation stage, encouraging vaccinations will more likely involve those in Preparation, since the inescapable circumstances of the pandemic have made the public aware that they need to make a decision about the vaccine.

When individuals are in the Preparation stage, they are actively working toward making a decision by analyzing the situation at hand, evaluating their options, and weighing the pros and cons of the potential decision. As such, this group is the main focus of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ vaccine safety campaign.

Calling them the “movable middle,” the campaign aims to influence Americans who are preparing to make a decision on the vaccine. This focus on those in the Preparation stage rather than those who have already decided against the vaccine (such as “anti-vaxxers”) will ultimately be more cost-effective and impactful.

Public health messaging strategies

Since the “movable middle” are those who are weighing their options, campaigns should focus on emphasizing the benefits of making the desired decision and on mitigating any concerns. However, while vaccines may be designed for the masses, the messaging for these campaigns definitely should not be. As with any marketing campaign, segmenting the market and creating tailored messaging will be necessary for the marketing effort to succeed.

While vaccines may be designed for the masses, the messaging for the campaigns should not be.

Segmenting based on unique identities

Understanding the hesitation behind getting vaccinated must go beyond the surface-level concerns stated. Two segments of the population could express concerns over the vaccine’s side effects but then have completely different reasons as to why.

The Black community, for example, has historically distrusted the healthcare system in the US due to “unequal healthcare access and treatment, under-representation in clinical trials and a history of medical horror stories, such as the infamous ‘Tuskegee Study,’” as reported in U.S. News. Messaging tailored to the Black community, then, will differ greatly from messaging targeted to a community whose concerns are rooted in a lack of understanding of vaccines. Identity must be strongly considered in segmentation strategies and each segment’s differences must be acknowledged through tailored messaging.

Establishing trust and understanding

These defined segments should also be considered in efforts to establish trust. Because trusted messengers are needed to effectively connect with an audience, influential figures that are relevant to each segment will prove invaluable to campaign efforts. Elvis Presley, for example, was key in encouraging children and young adults to take the Polio vaccine back when trust in the vaccine was low after an isolated distribution incident left children infected.

Additionally, the language used must fit the audience. The average person does not easily understand medical terminology or statistics. Providing clear and honest information using layman’s terms, analogies, and stories is much more effective at encouraging trust and understanding than unfamiliar technical jargon. Krispy Kreme’s announcement this week that they’ll give a free donut to anyone vaccinated through 2021 may not be a deciding factor in vaccination plans but further establishes trust coming from an enduring national brand with a loyal customer base.

Avoiding contradictions and ultimatums

While transparency is crucial in public health messaging, we also have to avoid the tendency to put out contradictory messages by highlighting potential drawbacks too strongly. This has been especially true with the vaccine. Because its crucial benefits (lowering the risk of severe symptoms and death) have been communicated alongside its shortfalls (the possibility of asymptomatic spread and mild infections), those trying to make a decision regarding the vaccine have become confused and distrusting. As neuroeconomist Uma Karmarker mentioned, “The messaging that the vaccine will fix things – but also that the vaccine is not good enough – is in seeming conflict.”

Overall, framing decisions in a binary manner is seldom the way to go. Most consumer brands understand the power of choice and rarely offer their customers just one or two options. Take the classic coffee shop example. By offering multiple coffee sizes, the customer is subconsciously encouraged to reframe the decision they need to make from “Should I buy coffee or not?” into “Which size coffee should I buy?”

Unfortunately, when it comes to public health, circumstances and decisions are often presented in a binary “all or nothing” manner. Either you wear a mask or you don’t. Either you get the vaccine or you don’t. This approach frames making a decision as having to choose between two extreme yet seemingly equal ends, which not only gives power to the undesired behavior but may also paralyze individuals from deciding at all.

Nudging the public to consider 3 choices — getting vaccinated now, getting vaccinated later, or not at all — will lead many to opt for the middle “compromise” choice.

Instead, in order to encourage a decision or behavior change, a “compromise” option could be presented so as to frame the desired decision as less extreme. For example, nudging the public to consider three choices — getting vaccinated now, getting vaccinated later, or not at all — will lead many to opt for the middle “compromise” choice, which still results in the desired behavior of vaccination.

Ultimately, changing public health behavior is a matter of understanding what stage of readiness the public is in ahead of making a decision and implementing change. The identification of that stage will determine the focus and goals of efforts to push them through the process of decision-making and change. From there, effective public health messaging will involve deeply understanding target segments, establishing trust and understanding, and tactfully framing the situation in a way that avoids binary decision-making and encourages choice.

Photo by Aaron Sousa

Ask for help.

We are kind, thorough and ready when you are. You just need to ask.